Watts Towers Arts Center Campus

Established in 1961, the Watts Towers Art Center is a cultural and educational center, and the longtime steward of Simon Rodia’s singular installation Nuestro Pueblo, or Watts Towers. The Center provides classes, including painting, sculpture, photography, music, dance, gardening, tiling, and other multi-media arts, taught by professional artists, as well as tours, lectures, and exhibitions that attract local, national, and international visitors. The Center also produces two yearly festivals – the Watts Towers Day of the Drum Festival and the Simon Rodia Watts Towers Jazz Festival. Through all of its offerings, the Center has presented over 1,000 artists in numerous disciplines including, visual arts, filmmaking, writing, music and performing arts. In addition to its educational and programmatic offerings, the Watts Towers Arts Center serves as an integral hub in the Watts community, nurturing artists and acting as a conduit for social change.

North House Folk School

North House Folk School was founded in 1997 with a dedication to traditional craft and cooperative learning. The school’s mission is to “enrich lives and build community by teaching traditional northern crafts in a student-centered learning environment that inspires the hands, the heart and the mind.” The school has grown over the years, and now hosts over 3,000 students per year and offers over 350 classes. Located in the Northwoods of Minnesota, on the shore of Lake Superior, it is one of the few places where Scandinavian timber framing is being practiced and taught.

Haystack Mountain School of Crafts

Haystack Mountain School of Crafts is an international craft school located in Deer Isle, on the coast of Maine. Founded in 1950, “Haystack,” as it is popularly known, is located on the coast of Maine in Deer Isle, and welcomes students of all skill levels to participate in their one and two-week studio workshops and the two-week Open Studio Residency program. Haystack also offers exhibitions, tours, auctions, artist presentations, and shorter workshops for Maine residents and high school students. The school supports visiting artists and scholars from a variety of fields, and explores the scholarly aspects of craft, by publishing annual monographs and organizing a variety of symposia that examine craft in broader contexts.

Haystack’s mission states that it “provides the freedom to engage with materials and develop new ideas in a supportive and inclusive community. Serving an ever-changing group of makers and thinkers, we are dedicated to working and learning alongside one another, while exploring the intersections of craft, art, and design in broad and expansive ways.”

Berea College

Berea College is a private liberal arts work college in Berea, Kentucky. Founded in 1855, Berea College is recognized for its no-tuition promise, providing free education to every student. The College has been a leader in the Appalachian Crafts movement since the 1890s, when it established the Berea Student Craft Program. Beginning with Weaving in 1893, the school has since added Woodcraft in 1895, and Broomcraft and Ceramics in 1920. The Student Craft Program is a part of Berea’s broader Labor Program, which requires every student to contribute to the operations of the school through a number of job opportunities, including craft. Over 100 students work in the Student Craft Program, and their work is available for sale in person and online through the Berea College Visitor Center and Shoppe. All proceeds go back to supporting Berea College programs and its Tuition Promise.

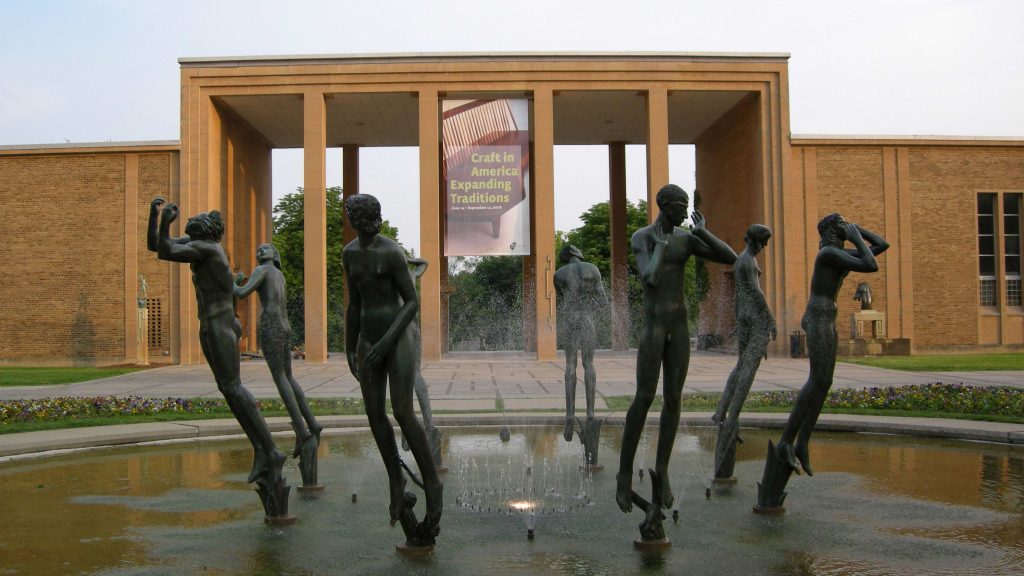

Cranbrook

Cranbrook was founded in 1932 by George and Ellen Booth in Bloomfield Hills, MI. Cranbrook is comprised of a graduate Academy of Art, an Art Museum, House & Gardens, Institute of Science, and Pre-K through 12 college preparatory school.

Many of the buildings were designed by Finnish architect, Eliel Saarinen. At the Cranbrook Academy of Art, the graduate students learn through a personalized course of study. There is no formal class structure but an active program of studio work, critiques, reading groups/seminars, and student group projects. They offer study in the following areas: Architecture, Ceramics, Fiber, 2-D Design, 3-D Design, Metalsmithing, Painting, Photography, Print Media, and Sculpture.

Black Mountain College

Black Mountain College was an experimental school founded in the middle of the twentieth century on the principles of balancing academics, arts, and manual labor within a democratic, communal society to create “complete” people. The environment was so conducive to interdisciplinary work and experimentation that it proved to be one of the most important settings for twentieth-century artists in their quest to revolutionize modern art.

Many of the school’s faculty and students were or would go on to become highly influential in the arts, including such people as Josef and Anni Albers, Ruth Asawa, Walter Gropius, Robert Motherwell, Dorothea Rockburne, Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg, Merce Cunningham, John Cage, Buckminster Fuller, Franz Kline, Willem and Elaine de Kooning and Allen Ginsberg, among others.

While Black Mountain College existed for only twenty-four years from 1933 to 1957, it left an indelible mark on the American art scene. Today, the Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center (BMCM+AC) preserves and continues the unique legacy of educational and artistic innovation of Black Mountain College and achieves this mission through collection, conservation, and educational activities including exhibitions, publications, and public programs.

Penland School of Crafts

Penland School of Crafts, located in North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains, was founded as a national center for craft education in 1929 by Lucy Morgan. It is one of the oldest and most prestigious handicraft schools in America.

Miss Lucy, as she came to be known, first came to Penland, North Carolina in 1920 as a teacher. After attending historic Berea College in Kentucky for some months in 1923, she returned to Penland with a commitment to preserve the local art of hand-weaving and improve the lives of her community, in accord with the prevailing philosophy of the Arts and Crafts movement. There, she established a cottage industry initially called the Fireside Industries, then the Penland Weavers and Potters, then the Penland School of Handicrafts, and today, the Penland School of Crafts.

In 1928, Edward F. Worst, a weaving expert from Chicago, inaugurated his annual summer workshops with the weavers. News of his work at the school was announced in the prestigious Handicrafter magazine, bringing renown and for the first time, students from outside the county to attend the school.

Classes in basketry, pottery, silversmithing and metalwork were added, and in 1929, the Penland School of Handicrafts was officially founded.

The success and recognition of Penland lay in Lucy Morgan’s unbounded energy and enthusiasm. She traveled to Washington, DC to meet with the National Park Service to discuss the sale of crafts at National Parks, transported and sold crafts at the Chicago World’s Fair, and represented the Southern Mountain Handicraft Guild at the International Exhibition of Folk Arts in Berne, Switzerland. By the mid 1940s, visitors from Canada, Peru, China, Mongolia, and Africa came to learn about this extraordinary cottage industry.

By the time Lucy Morgan retired in 1962, enrollment had declined, but the incoming Director, sculptor and design teacher Bill Brown shared a devotion to experiential education, bringing with him a new energy and network of connections to the growing studio craft movement. Brown added new media and expanded the programming.

Penland School of Crafts was one of the first schools in the country to teach the art of glassblowing, a pursuit that had attracted such artists as Harvey K. Littleton, Mark Peiser, and John Nygren.

Classes, taught by visiting professors and artists from all around the United States, are offered in the Spring, Fall, and Summer in a variety of media, including pottery, glassblowing, metalworking, weaving, as well as painting, photography, and printmaking; however, academic degrees are not awarded.

There is an excellent Resident Artist Program. Many students go on to pursue their craft on a professional level and have achieved critical acclaim after leaving Penland. On Community Day in early March, Penland opens its studios to visitors who can work on a small project with the help of the artists.

Penland School began out of a strong belief in a few simple values which have guided it throughout its history.

The joy of creative occupation and a certain togetherness – working with one another in creating the good and the beautiful. – Lucy Morgan

Archie Bray Foundation for the Ceramic Arts

The Archie Bray Foundation for the Ceramic Arts is a public, nonprofit, educational institution founded in 1951 by brickmaker Archie Bray, who intended it to be “a place to make available for all who are seriously interested in any of the branches of the ceramic arts, a fine place to work.” Its primary mission is to provide an environment that stimulates creative work in ceramics.

The Bray, located in Helena, Montana, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and recognized as a gathering place for emerging and established ceramic artists with a dynamic arts community created by the resident artists that come to the Bray to work, share experiences, and explore new ideas.

Pilchuck Glass School

Pilchuck Glass School was founded in 1971 by Dale Chihuly, Anne Gould Hauberg, and John H. Hauberg. Through the years, Pilchuck has been a primary force in the evolution of glass as a means of artistic expression and has become the largest, most comprehensive educational center in the world for artists working with glass.

Pilchuck’s philosophy of education flows from Dale Chihuly’s original idea of “artists teaching artists.” It stems from the belief that people everywhere thrive on creativity and can learn to cultivate their artistic talents, at any stage of life and at any point in their development as artists. In keeping with that belief, Pilchuck provides a learning experience unrivaled in its intensity, quality of instruction, and concentration of artistic talent.

That founding summer Chihuly was accompanied by two other teachers and sixteen students. When the students arrived, their first project was to build glory holes and a furnace. They began blowing glass just sixteen days after arriving. The artists also designed and built their own houses — the first year these were mostly plastic tarps draped over planks; the second year more substantial houses were built.

By nature, glassblowing requires teamwork but the generous spirit the school embraced was special. Collaborative glassmaking became known as “the Pilchuck way,” explains current Pilchuck executive director Jim Baker, who adds that also integral to Pilchuck’s success was an early commitment to freedom of expression. “Pilchuck immediately threw people into experimental mode.”

The school quickly became recognized as one of the top programs in the world for glass artists. Through trial and error, artists invented new forms and glassworking methods, and as this continued, the studio glass movement evolved.

In the late 70s Pilchuck began to invite renowned makers from different glass centers around the world to teach their (formerly) proprietary methods of glassmaking. This led to a new wave of students and artists learning and openly sharing a wide range of techniques.

In the 80s, Pilchuck began to invite influential contemporary artists renowned in other media to learn how to use glass in their work.

The fundamental mission at Pilchuck has been to act as a learning, experimentation and research facility and to serve as an advocate for glass as a medium.

Pilchuck’s artistic and educational programs take place primarily on a serene sixty-acre wooded campus fifty miles north of Seattle. Pilchuck now offers 35 intensive residential sessions from April to September. Students work in hot and cold glass techniques including glassblowing, casting, fusing, neon, stained glass, painted glass, flameworking, mixed media sculpture, and engraving.

In addition to the Stanwood campus, Pilchuck also has an exhibition and administrative office space in Pioneer Square; the commercial and artistic core of downtown Seattle.

Salem Community College

New Jersey’s Salem Community College, which opened as the Salem County Technical Institute in 1958, offers the only Scientific Glass Technology associate degree program in the United States. This degree provides students with the necessary skills and techniques to construct scientific glass apparatus for university laboratories, industrial research and production.

SCC also offers degrees in Glass Art and Industrial Design. In the Glass Art program, students learn mold-making, glass casting, fusing and slumping, hot glassblowing, lampworking and cold-construction techniques. The Industrial Design program combines the creative processes with the business and technical skills needed to design glass products and to have a successful career as a glass artist. SCC alumnus, adjunct professor and artist-in-residence, Paul J. Stankard, also chairs the College’s annual International Flameworking Conference.

www.salemcc.edu/glass/conference