Memory: Hand to Home

Some hands create to record a place and time; others are more intimate gestures about personal histories. In any case our Nation’s collective memory can become tangible when we examine objects created by the hand. This educational guide helps develop craft in a larger context, providing educators with material that will relate to and reflect the core ideas and art forms presented in the MEMORY episode.

Download Education Guide & Worksheets

Craftspeople find pleasure and fulfillment in making objects that are beautiful, unique, and functional. Many craft artists think about these notions of beauty and function and work tirelessly to realize their visions. In this section of Education Guide: MEMORY, students will deepen their knowledge and understanding of how artists use their most valuable tool, their hands, to transform raw materials into works of art that are meant to used and enjoyed by those who own them.

Featured Artists

Sam Maloof (woodworker/MEMORY)

Sarah Jaeger (potter/COMMUNITY)

Related Artists

Mississippi Cultural Crossroads (quilting/COMMUNITY)

Hystercine Rankin (quilting/COMMUNITY)

There are certain qualities that I aspire to in my work–it’s that elegant folky thing which to me implies making work that is useful and beautiful.

– Sarah Jaeger

Hold up your hand. Look closely at its size, shape and lines. What does it reveal about you? About where you’ve been? What you’ve done? What memories does it hold? Our handprints are unique–our one-of-a-kind signature. In the world of craft, the artist’s hand is also unique–a part of every work he creates. Whether a basket, a teapot, a quilt, or a chair is being made, the hand helps the artist realize her vision—it’s one of her tools. It pulls the sweet grass reeds taunt, forms the clay on the wheel, pushes the needle through the cloth and guides the wood along the edge of the saw blade. Without this tool, the artist’s vision would not emerge from the materials. The hand of the artist also embeds meaning into every object, making that object special and unique.

The need to create, to make beautiful, functional objects draws craft artists into their studios. Every day they engage in this ritual of making–they repeat the same processes in order to transform their materials, realize their visions and master their crafts. Objects emerge from their hands, giving them great pleasure and satisfaction. As they work, they are also aware that they are making things that will be used—in fact, they want them to be used. As they weave, shape, sew, and cut, they have the users in mind. This is an important aspect of their work. They know that their artworks will soon find homes where they will be used and cherished. They hope their objects will contribute to the character and spirit of those homes. From the hand of the maker, to the home of the user, every craft object is transformed by those who touch it. This unique connection between the maker, the user, and the object cannot be undone.

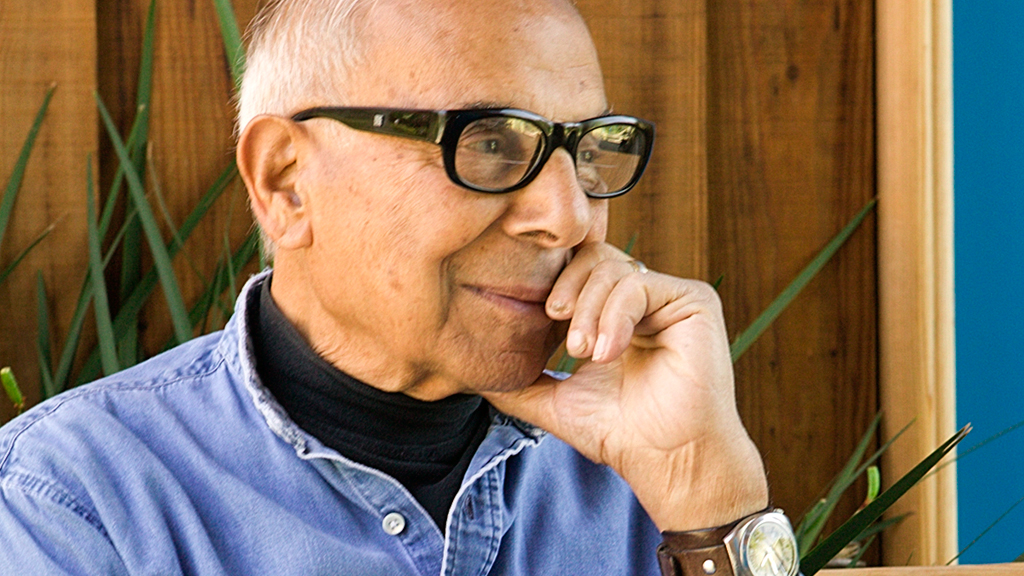

Letting Go: Sam Maloof

Before he passed in 2009, ninety two year old woodworker Sam Maloof worked in his studio six days a week. With his team of master craftsmen, David Wade, Mike Johnson and Larry White whom he affectionately called “the boys,” Maloof spent his days making beautiful, distinctive furniture as he had done for over fifty years. While Maloof’s chairs are solid enough to withstand the test of time, he also insisted that they look good and be comfortable. As each one takes shape, Maloof paid careful attention to every detail–selecting the wood, overseeing the design and carving his signature into the underside. He was uniquely in command of every aspect of his craft.

He loved to see the personality of each piece of wood come to life as it transformed into a finished chair or table. The warmth and sensuous nature of the wood inspired him; he found pleasure in seeing it emerge from skilled, experienced hands. He also found pleasure in meeting the people who will own his furniture. If the client likes it, Maloof said he is paid ten-fold. He knew that despite the countless hours spent creating these custom-made objects, they need to let them go when they are finished. It was very important to him that his clients experience pleasure from their purchases in the same way he enjoyed making them. There is special relationship between Maloof and every piece he has crafted over the years. He remembers each one fondly, but he lets his “children” go so they can begin their lives in homes where they will be loved and cherished.

Sam Maloof

1916-2009, Chino, California

• Self-taught woodworker

• One of the most celebrated and respected contemporary furniture craftsmen

• Began making furniture out of necessity for his wife Alfreda in the late 1940s using scrap railroad wood

• Nearly sixty years later, makes furniture out of the finest woods, with a typical piece costing thousands of dollars

• Relationship with wood began when he carved toys for himself as the young son of Lebanese immigrants

• Maloof Woodworking continues to create furniture in his studio in Alta Loma, California

• Work is world-renowned and can be found in collections at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Los Angeles County Museum of Art, The Smithsonian, the White House, and in many other museum and private collections

• He refers to himself as a woodworker, rather than an artist

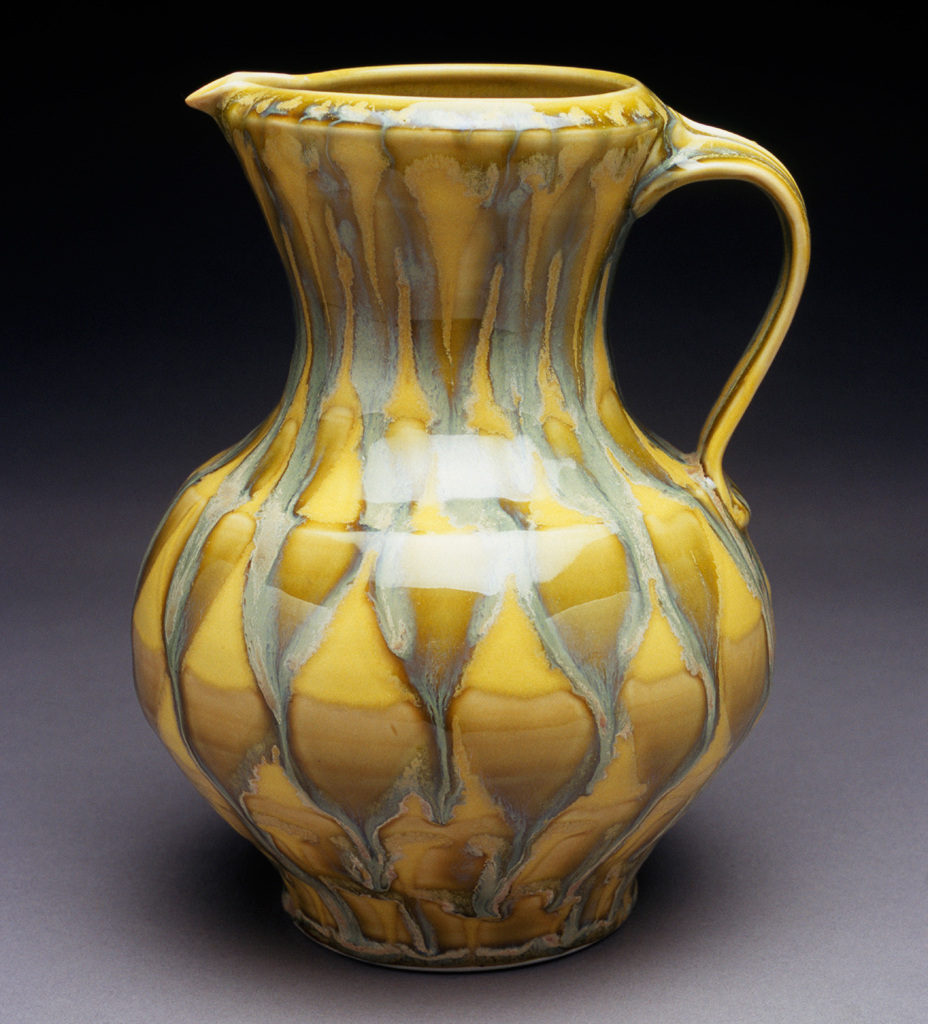

The Town Potter: Sarah Jaeger

Sarah Jaeger finds pleasure in being known as the “town potter.” Each day she works in her Helena, Montana studio creating elegant and folky pots she knows will leave her hands to grace someone else’s home. Jaeger loves the physicality of her work–the feel of the clay, the varied pressure she must apply as the clay spins on the wheel, the simple, elegant handles she arcs just so. All aspects of her work involve her touch, guidance and vision. As her hands gently transform the clay into teapots, cups, and other functional vessels, Jaeger pays a great deal of attention to every detail, constantly keeping the user in mind as she works. She finds it satisfying to get feedback from people who use her pieces as part of their daily lives. Jaeger knows that her beautiful work must have a utilitarian function.

Jaeger knows how to make pots that combine her vision with the user’s need. She understands that the use of a handcrafted cup for your morning coffee or bowl for your soup provides nourishment on many levels. People eating and drinking together is an important act, part of our daily lives, and Jaeger’s beautiful pots transform the daily routine of eating from ordinary to extraordinary. She nourishes the body and the soul through the simple act of making beautiful objects that she shares with the world.

Sarah Jaeger

Born 1949, West Simsbury, Connecticut

• Studio potter living in Helena, Montana

• Creates pots for everyday use

• Discovered clay while earning her BA at Harvard University and continued artistic studies at the Kansas City Art Institute, earning a BFA

• Moved to Helena to become a resident artist at the prestigious Archie Bray Foundation for the Ceramic Arts

• “The greatest compliment someone can pay to me is say, ‘We open the cupboard in the morning, and we always reach for your cups when we are going to make coffee.’ I’d rather know that than know that a piece is on a pedestal in a museum.”

• Work can be found in kitchen cabinets everywhere, and in museum and private collections throughout the country

The Craft Connection

As craftspeople, Sam Maloof and Sarah Jaeger find pleasure and fulfillment in making objects that are beautiful, unique, and functional. Both artists use their hands to transform raw materials into works of art that are meant to used and enjoyed by those who own them. From their hands to the owner’s home, each teapot and chair created is part of a daily ritual that includes time in their respective studios perfecting their craft and thinking about who will use each object that leaves their hands. Many craft artists, like Maloof and Jaeger, think about the notions of beauty and function and work tirelessly to incorporate them into their visions.

View

Have students watch the DVD segments featuring Sam Maloof and Sarah Jaeger or view online at www.craftinamerica.org/short/sam-maloof-segment and www.craftinamerica.org/short/sarah-jaeger-segment. Ask them to consider this question while viewing: What is important to each of these two artists?

After viewing, discuss what the students noticed. Give each student a copy of Handcrafted (Memory: Hand to Home Worksheet #1) and duplicate the diagram on the white board. As a class, complete the diagrams. Prompt students with question such as: Does the artist have a routine way of working? How important is this routine to the artist? Does the artist care about the person who will use the object? How important is this to the artist? What did you see during the DVD segment to support your ideas? How important is it to each artist that the object made functions as they intended (i.e., a teapot holds and pours tea, a chair is comfortable to sit in, a cup fits in the hand, etc.)? What about beauty?

Watch the DVD segments a second time. Ask students to consider the following question: How are materials transformed by the hand of the artist?

After the second viewing, discuss what the students noticed. Use Ritual and Routine (Memory: Hand to Home Worksheet #2) to compare and contrast the artists’ respective ways of working. Prompt students with questions such as: What are the materials? What tools are important? What steps are involved in the process used by each artist? Does the artist work alone? Why or why not? What studio space is necessary to work? How do these artists earn a living, given that they both do this full-time? How do these two artists indicate that their work is ready to leave the studio?

Explore

As a group in class or individually at home, have students watch additional DVD segments that feature artists working in their studios. Possible artists include, but are not limited to: Dona Look and Ken Loeber (jewelry/COMMUNITY), Mary Jackson (basket maker/MEMORY), and Einar and Jamex de la Torre (glass/COMMUNITY). Have them consider each artist’s required space, tools, and overall art-making environment. Prompt their viewing with such questions as: What are the materials? What tools are important? What steps are involved in the process used by each artist? Does the artist work alone? Why or why not? What studio space is necessary to work? What seems to be important to each artist in terms of her working environment? How do these artists indicate that their work is ready to leave the studio?

Explore

Have students find out more about how craft artists earn a living. They should explore annual craft shows through the American Craft Council Web site: www.acc.org. Are there craft organizations and venues in their area? Where do local craftspeople sell their work?

Investigate

Print copies of the short story “Everyday Use” by Alice Walker from .

Have students read the story, then engage them in a discussion about what they read. Why did Maggie want the quilts? Why did Dee (Wangero) want the quilts? Who should have the them and why?

Make

A Three-Part Making Experience

Part 1: User Unknown

Have the students make a functional clay object such as a hand-built pinch, coil, slab, or wheel-thrown cup or bowl. Emphasize that this object is something that will be used by someone, but that person is unknown. This object could be made for sale at a local craft fair, or all the objects made could be sold as a fundraiser for the school, the class, or some other cause. Review with students the maker’s considerations: type of use, weight (density), texture, usability (how it feels in the hand, whether it stands on its own or needs a lip, size of object relevant to intended use), color, where the signature will appear, how it will be displayed for sale, and price.

Part 2: Crafted with Care

Ask students to remember something they were proud to have made by hand, such as an elementary-school artwork. Did you give it to someone? How did that person respond? What happened to the object? Why do you still remember this object? Do you think the recipient remembers that you made it? Help students understand that handmade objects are generally seen as special–we often save what people make for us. Have you ever been given something handmade? Why is it special to you? Would it be different if it was store-bought?

Now have students make a second functional clay object, deciding who it is for before they begin (e.g., a classmate, teacher, friend, family member, or other important person). This could be the same kind of object made in Part 1, or they could change it (e.g., make a cup instead of a bowl).

Part 3: From Hand to Home

Have students place both objects made in front of them, and consider the following questions: Why did you create these particular types of objects? How did the intended user influence that choice? What did you do differently in each instance? How did knowing the identity of the user influence decisions about how the object’s look? Was one of the objects more difficult to make than the other? Why or why not? Did you feel differently making the second object than you did making the first? Were you thinking about the recipient while making the second object? Did one take longer to make than the other? Why or why not? Which one were you happier with? Are you looking forward to sending these objects out of the studio?

Reflect

Take the conversation back to the larger theme presented using Hand to Home: A Scenario (Memory: Hand to Home Worksheet #3).

Craft in Your World

Seek the truth in materials. How can you tell if wood is real or not? What qualities does real wood present? How many objects can you find that are made out of simulated wood? Why do people want products made of “fake” wood?

We use cups, bowls, and plates every day. Have students go home and look in their cupboards to see if there are any handcrafted cups or dishes. How can you tell if it’s handmade or not? Many designers try to make their products look handcrafted. Why?